Why Bright Kids from Low-Income Homes Lose Ground—and How to Stop It

Between ages 11–14, many bright low-income students lose ground. Here’s why it happens—and how parents can keep brilliance on track.

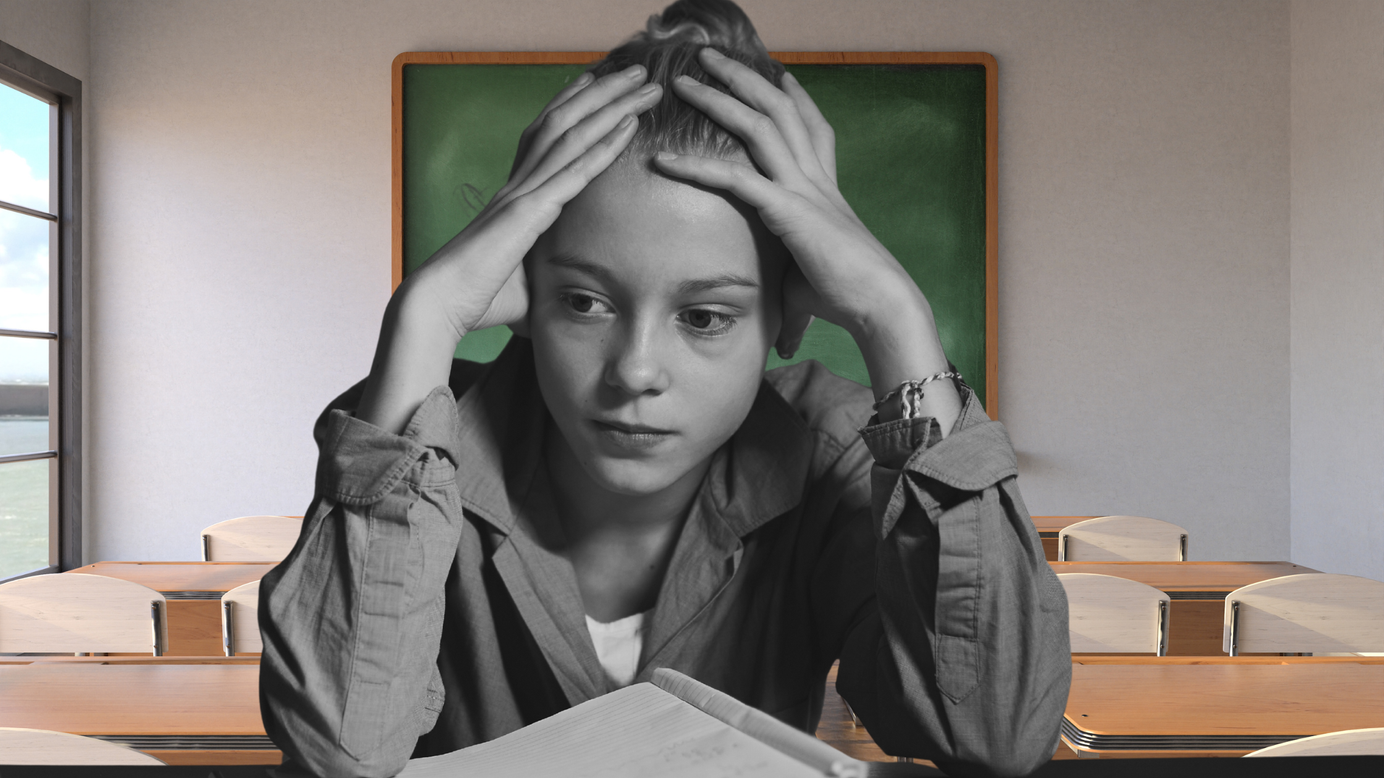

In primary school, high-ability kids from low-income families often keep pace with their wealthier peers. But something happens in the first years of secondary school (ages 11–14).

Motivation dips. Behavior issues tick up. Mental health struggles rise. Grades slide fast.

This isn’t a story about ability. It’s a story about timing. The “cliff” is real, but with the right support before and during this transition, it can be flattened.

What the Research Shows

A major UK study followed children from age 5 to 16. It found no significant gap between bright children from poorer and richer homes by the end of primary school.

The divergence appears after the move to secondary school: disadvantaged high-achievers report sharper drops in school engagement, mental health, and behavior. By age 16, they are ~26 percentage points less likely to earn top marks in maths and ~21 points less in English compared to equally bright peers from high-income families.

In the US, the story is similar—and getting worse. The income-achievement gap is now 30–40% larger for children born in the early 2000s than for those born just a generation earlier.

Why the Gap Widens

Same child, tougher context. Secondary school often means bigger classes, more teachers, higher academic demands, and new social pressures. Without targeted support, these changes amplify resource gaps.

Mental health load. Economic stress increases the risk of anxiety, depression, and behavior problems by 2–3×. Those risks grow over time and can drain the motivation that drives learning.

Brains under strain. Poverty is linked to differences in brain development, especially in areas for learning, memory, and self-control. These gaps can explain up to 20% of achievement differences. The good news: environment and support can make a measurable difference.

What Parents Can Do (Ages 10–14)

- Pre-wire the transition. Visit the new school together. Identify a safe adult on campus. Ask how they challenge and support high-ability, low-income students.

- Protect the basics. Keep bedtimes steady, limit screens during study, and set a weekly routine that blends practice with curiosity-driven learning.

- Build a micro-village. Have at least two other adults on your child’s “team” (e.g., a teacher champion and a mentor). Steer them toward clubs or activities that affirm their identity and effort.

- Watch for red lights. Listen for “school is pointless,” spot changes in friend groups, track missing work in core subjects, and take headaches or stomachaches seriously—they can be stress signals.

- Treat mental health like a core subject. Normalize counseling checkups. Ask schools about free or low-cost services. Early help prevents later setbacks.

What Schools and Systems Can Do

- Name the cliff. Track high-ability, low-income students from the end of primary through Year 9. Monitor attendance, behavior, and participation; not just grades.

- Engineer continuity. Align curriculum between primary and secondary. Run bridge programs that mix academic refreshers with social-belonging activities.

- Guarantee a champion. Every flagged student gets a named adult and access to an identity-affirming extracurricular.

- Prioritize mental health. Embed school-based counseling hours and make referrals easy for families under financial stress.

- Fund the peak years. Early education investment is essential—but don’t neglect the middle-school years, where the cliff actually appears.

How It Fits Our Framework

- Discover early signs of decline in engagement and well-being—not just grades.

- Develop scaffolds that challenge students while reinforcing belonging.

- Direct their talents toward selective pathways and future opportunities before options narrow at 14–16.

Bottom Line

The 11–14 transition can be a turning point for better or worse. If we act early and with intention, we can keep brilliance on track.

No wasted talent. No quiet slide.

GiftedTalented.com

The world's fastest growing gifted & talented community